Family Field Day 2025

Dear friends and neighbors,

What a day.

We’re so grateful to everyone who came out to walk, rest, reflect, and share time on Karol’s Prairie. Our little 45 acres is slowly coming into its own, guided by wind, hoof, and fire. Thanks to our cows (and their surprisingly effective mowing), the picnic area and hiking paths were more accessible than ever this year.

About 50 of you joined us, making space for deep conversation and easy reconnection. Around half walked the 1-mile loop and visited all six stations, each one inviting a different way to see the land:

The Wellhead, where restoration begins with water.

The Fallen Cottonwood, still teaching us after it fell.

The Dugout, a reminder that not all legacies age well.

The Badger Hole, where unseen lives make the surface possible.

The Missing Branch, carried by the flood, rested where water left it.

The Burned Triangles, where fire coaxed sleeping seeds back to life.

We’ve left the stations up in case you’d like to return or bring someone new along for the walk.

We were moved (and honestly, overwhelmed) by how many neighbors offered fieldstone and cattle panels to help us build the gabion walls for our entrance. If you still have stone or panels to share, feel free to drop them just inside the south side of the gate, or let us know where to pick them up. We’re also looking for larger timber, old power poles, or barn beams, for future benches and signage.

And if you haven’t yet seen the cut steel sign on 449th Street at the gate, stop by sometime. It will be permanently mounted to the gabion wall, serving as a marker for something growing, not just a built structure.

Thank you for walking with us on the prairie and in this shared work of restoration.

We hope to see you next year, on the second Saturday in June. Until then, may you continue to ask big questions… and listen closely to the land.

With gratitude and prairie dust,

Clinton Brown

Karol’s Prairie Stewardship Team

Birds of Summer

Well, we had some birders out today. They sent me this list of stuff they identified and maybe identified.

Birds at Karol’s Prairie

Canadá goose

Mallard

Ring-necked pheasant

Red headed woodpecker

Northern flicker

Brown thrasher

Western meadowlark

Dickcissel

Eastern kingbird

Barn swallow

Killdeer

Orchard oriole

Bobolink

House wren

Brown-headed cowbird

Warbling vireo

American Robin

Red-winged blackbird

Warbling vireo

Common grackle

Mourning dove

European starling

Upland sandpiper?

Yellow warbler?

Song sparrow?

Vesper sparrow?

The cows are off.

So because we could not burn the paddock that we wanted, we had our grazer intensely graze the same paddock.

2 acres of intense grazing. 10 cow/calf pairs.

You can clearly see the grazed area on the right. They have been off the grass for 8 days.

This small narrow strip, about .5 acres, had the cows for 4 days grazing, and now rested for 4 days. You can see the intense disturbance they caused. This is good.

New well motor

Well we had to invest in a new electric motor, which ended up needing a new larger generator. We gotta get those cows some fresh water. 10 pairs coming.

Checking on regrowth

It has been two weeks since the burn. I was curious to see how the regrowth is coming along. Because of the cold weather, I am concerned we have just given Brome a second chance. We shall see.

This is Daisy Duke. She is very stimulated by the water.

First Burn

Well when we got to the field, it has grown so much that we were unable to burn the pasture that we wanted to burn. We ended up burning one of the triangles of land that we co-manage with the Waltner family. It was a test to see how the weeds respond. The wind was less than ideal in that it kept changing directions.

We only burned .92 acres to test burning out here. We learned a lot. Shaded red.

Asleep and Hidden

It’s been a while since we visited the prairie and took photos. This is a very dry winter and we are concerned about spring growth.

Sleepy prairie

Sometimes we come out at night and just listen. The prairie has so much to say.

Let’s work on the well.

The well has been as frustrating as it is satisfying to see it run.

Tiny Mushrooms

We always look for fungal activity. Mushrooms tell us things. That decay is happening. That networks are in place. That the nutrient cycle is at work.

Fix fences for cows

Back for another round of fixing and replacing the fence that the water washed away.

Walking the land

I try to get out and walk the whole property a few times per year. This walk was different because we had near historic flooding just a few weeks ago. Our prairie became a temporary river. From May 15 through the end of June we had 30 inches of rain.

First Annual Family Field Day

Wow.

Really, I don’t need to write more. Yesterday was a day to remember. We had 55 neighbors show up to Karol’s Prairie and fill the air with stories, laughter, questions, and ideas. People who hadn’t seen each other in years reconnected, and it felt like a reunion of hearts and minds under the wide-open sky. The weather was perfect—a sunny June day, with just enough breeze to keep the bugs at bay. It was magical.

But what made the day even more special was the way people engaged with the land. Families spread out across the prairie, kids running through the grasses, their shouts blending with the calls of birds. Adults leaned in, listening as we talked about how Karol’s Prairie is more than just a pretty patch of land.

It’s easy to think of open spaces like this as "non-productive," but that couldn’t be further from the truth. Wild spaces, riparian zones, and prairies like this one are vital. They are the lungs and lifeblood of our ecosystem. These are the places that soak up rainwater, purify it, and slowly release it into creeks and rivers. They provide habitat for pollinators and wildlife, which are essential to agriculture. They build resilience against flooding, drought, and erosion.

When we prioritize these spaces—when we let them thrive—we’re not just preserving beauty. We’re preserving the foundation of a healthy, functioning landscape. Without these wild areas to balance the equation, the agriculture we depend on can’t survive.

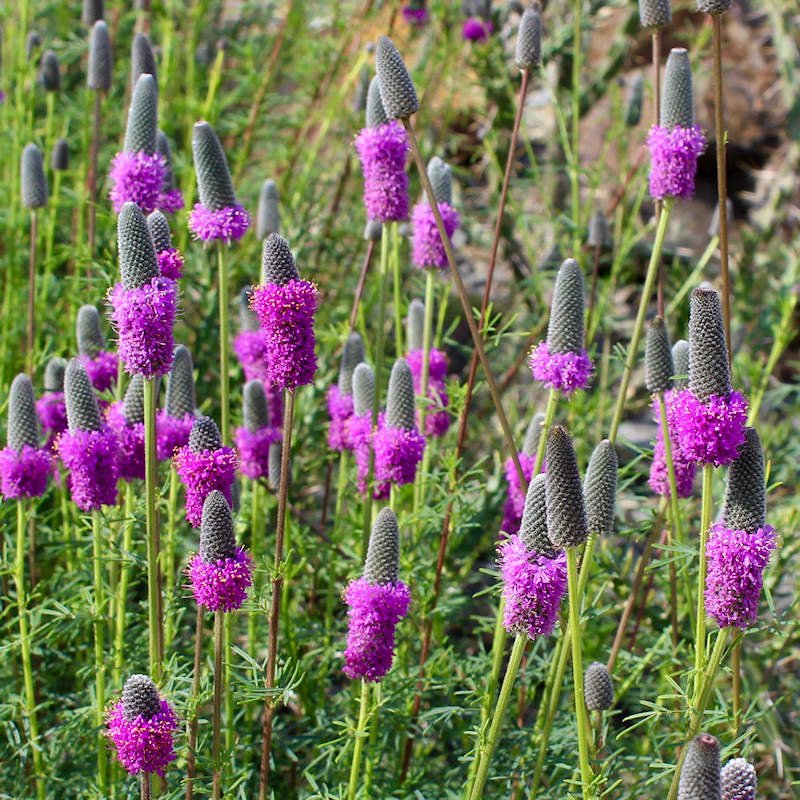

Yesterday, we shared some hands-on techniques to restore health to overworked or damaged land. Neighbors learned about native plants and how their deep roots hold soil and retain water. We talked about how allowing the land to regenerate itself over time strengthens not just the prairie, but also the farms and communities that surround it.

Getting people out in nature is one of the best ways to open their eyes to these ideas. Standing knee-deep in wildflowers and feeling the prairie wind reminds us that we’re part of this ecosystem, not separate from it. Watching kids discover a hidden frog or adults marvel at the deep roots of switchgrass makes the connection clear: what’s good for the land is good for us, too.

By the end of the day, it was clear we had planted more than just native seeds. We had planted the seeds of connection—to the land, to each other, and to a shared vision for a healthier, more resilient future.

Thank you to everyone who came out, asked questions, and shared your hopes and ideas. Thank you for reminding us that Karol’s Prairie isn’t just a project; it’s a place where community can grow.

If you missed this year’s field day, don’t worry—there will be more chances to get involved. Karol’s Prairie has big dreams for the future, and we’d love to have you be a part of them.

Until then, take a moment to step outside, breathe in the fresh air, and remember: the wild spaces are still here, quietly doing their work, waiting for us to join them.

For the birds

We decided to go out and do some bird identification. We used MerlineID to help as they are hard to spot in the tall grass.

Red-winged Blackbird

Dickcissel

Brown-headed Cowbird

Western Meadowlark

Northern House Wren

Mourning Dove

Eastern Kingbird

Bobolink

American Robin

Song Sparrow

More field day prep

We headed back out to make sure everything was set to go. Our animal neighbors were clearly ready for a good party.

Prepping for Family Field Day

We did some trail cutting getting ready for Family Field Day. Everything is so green! It was too deep to mow so I just pushed the brush cutter through the grass.

Winter mushroom hunting

It has been a dry and warm winter. We decided to come out and do some exploring to see what dried fungi we could find.

It’s time for a well

We finally decided to see what is going on under the old windmill that fell down and the well head that was damaged. Our friends from Koranda Well came out with their new truck to help pull out the old equipment and check the casing.

Cold Stratification for 2024

It’s true. I spread 5 acres of seed on the prairie on Christmas Eve. It started raining in the afternoon on the 23rd and quit raining just about the time we arrived on the 24th at noon.

Weather on the prairie on 12/23/23.

Weather on the prairie on 12/24/23.

We purchased 5 acres of seed from Pheasants Forever.

This 18 species Pollinator mix designed to meet SD CP42 Pollinator standard in MLRAs on Loamy soils. Updated Jan 2023.

Alfalfa (VNS) (0.62), Wild Bergamot (0.05), Blanket Flower (0.35), Prairie Cinquefoil (0.01), Prairie Coneflower (0.15), Illinois Bundleflower (0.36), Indian blanket (0.43), Common Milkweed (0.09), Purple Prairie Clover (0.19), White Prairie Clover (0.08), False Sunflower (0.18), Maximillian Sunflower (0.24), Black-eyed Susan (0.08), Yarrow (0.04), Little Bluestem (0.46), Sideoats Grama (0.36), Slender Wheatgrass (0.35), Western Wheatgrass (0.49).

We own a commercial grade mister/spreader. This tool is great. You simply fill the top hopper with seed and walk around spraying it like you are a Ghostbuster.

I used my Strava app to ensure I recorded where I had been.

When I lay this data over my Google Earth paddocks you can see I was able to spread the seed pretty accurately from memory. There are no fences in this section so I had to go from memory as it was too cold to get my phone out and look at the map.

You can see from the following image that Christmas brought us the precipitation and cold to burry and encase the seeds for cold stratification.

Seed stratification is a process that involves subjecting seeds to a period of cold and moist conditions to break dormancy and promote germination. Many plant species, particularly those native to temperate climates, have evolved mechanisms to prevent immediate germination of seeds upon dispersal. This dormancy helps seeds survive unfavorable conditions, and stratification is a natural way to signal to the seeds that the conditions are suitable for germination.

Here's how seed stratification works and how it can be beneficial for prairie restoration:

Seed Stratification Process:

Collection: Seeds are collected from native prairie plants.

Cleaning: Seeds are cleaned to remove any debris, chaff, or other impurities.

Moistening: Seeds are moistened to initiate the imbibition process, where water is absorbed by the seed.

Cold Treatment: Seeds are subjected to a period of cold and moist conditions, simulating winter conditions. This cold period helps break dormancy by overcoming physiological barriers that inhibit germination.

Warmth: After the cold treatment, seeds are exposed to warmer temperatures to signal the end of winter and the beginning of the growing season.

Planting: The treated seeds are then planted in the desired restoration area.

Benefits of Seed Stratification for Prairie Restoration:

Increased Germination Rates: Seed stratification enhances germination rates by mimicking the natural conditions required for many prairie plant species to break dormancy.

Species Diversity: Different prairie plant species may have specific stratification requirements. By understanding and implementing seed stratification techniques, restoration efforts can promote a diverse array of native species.

Timing Control: Seed stratification allows land managers to control the timing of germination. This can be particularly important for prairie restoration projects where establishing a diverse and resilient plant community is a priority.

Improved Establishment: Stratified seeds are more likely to establish and grow successfully when planted in the appropriate environmental conditions, contributing to the success of prairie restoration efforts.

Using Seed Stratification for Prairie Restoration:

Identifying Species Requirements: Understanding the specific stratification requirements of target prairie plant species is crucial. Different species may have varying needs in terms of cold duration, moisture levels, and temperature fluctuations.

Timing: Implement seed stratification during the appropriate season. Cold treatment typically occurs during the winter months, followed by planting in the spring when conditions are conducive to germination and growth.

Monitoring Conditions: Regularly monitor and control the environmental conditions during the stratification process to ensure that seeds are exposed to the required cold and moist conditions.

Collaboration: Work with experts, ecologists, and local resources to gather knowledge about the specific requirements of prairie plants in the target restoration area. Collaboration can help tailor stratification techniques to the unique characteristics of the ecosystem.

By employing seed stratification as part of a prairie restoration strategy, land managers can enhance the success and diversity of native plant establishment, contributing to the overall health and resilience of the restored prairie ecosystem.

What we did was leverage the impending snowfall to our advantage.

Spreading seeds just before the first major snowfall of the season can mimic a natural stratification process in prairie restoration, particularly for plant species that require cold-moist stratification to break dormancy. This approach takes advantage of the cold temperatures and snow cover during the winter months to provide the seeds with the necessary conditions for stratification. Here's how this method can mimic natural seed stratification:

1. Seed Collection and Preparation:

Collect seeds from native prairie plants, ensuring that they are mature and have gone through their natural ripening process.

Clean the seeds to remove any debris or impurities.

2. Moistening the Seeds:

Before spreading the seeds, moisten them to initiate the imbibition process, allowing water to penetrate the seed coat.

3. Timing:

Choose the timing carefully to coincide with the natural timing of seed dispersal in the prairie ecosystem. Aim to spread the seeds just before the first major snowfall of the season.

4. Spread Seeds on Bare Soil:

Ensure that the seeds are spread over bare soil to make direct contact with the ground.

5. Snow Cover:

The snow cover serves as a protective layer for the seeds, providing insulation against extreme temperatures and creating a moist environment.

6. Cold Temperature Exposure:

As the seeds lay beneath the snow, they are exposed to cold temperatures. The cold treatment helps break dormancy by overcoming physiological barriers that inhibit germination.

7. Snow Melt:

When the snow begins to melt in the spring, it exposes the stratified seeds to warmer temperatures. This change in conditions signals the end of winter and the beginning of the growing season.

8. Natural Germination:

With the combination of cold exposure and subsequent warming, the stratified seeds are more likely to germinate naturally when the environmental conditions are favorable.

Benefits of Snowfall Seed Spreading:

Simulates Natural Processes: This method mimics the natural process of seed dispersal and stratification that occurs in many prairie ecosystems where seeds fall to the ground before winter.

Protects Seeds: The snow cover provides insulation and protection for the seeds against extreme temperatures, as well as potential predation by birds and rodents.

Moisture Retention: The snow layer helps retain moisture, ensuring that the seeds remain in contact with a consistently moist environment.

Timing Alignment: By spreading seeds just before the first major snowfall, the timing aligns with the natural cycle of many prairie plant species, optimizing the chances of successful germination.

Low-Cost Approach: This method is relatively low-cost and relies on natural processes, making it suitable for large-scale prairie restoration projects.

26m gallons of water collected

So far we have collected and allow 1.2m gallons of water to infiltrate into our prairie in 2023. Seems like a lot huh? The math is pretty simple.

45 acres = 1,960,200 Square Feet

1,960,200 x .623 (gallons of water per inch of rain per square foot) = 1,221,204 gallons per inch of rain

21.25 inches of rain x 1,221,204 = 25,950,597 gallons of water.

That’s 53 Olympic swimming pools.

Water infiltration into prairies from rainfall is a critical process that plays a fundamental role in sustaining the health and functionality of these ecosystems. Here are several important reasons why water infiltration is crucial for prairies:

Soil Moisture and Plant Growth: Water infiltration ensures that the soil in prairies receives an adequate supply of moisture. This moisture is essential for the germination of seeds, the growth of plants, and the overall health of the vegetation in the prairie ecosystem. Adequate soil moisture supports the diverse plant species that characterize prairies.

Groundwater Recharge: Infiltrated water moves downward through the soil and may contribute to the recharge of groundwater aquifers. This is especially important in maintaining a sustainable water supply for both natural ecosystems and human communities that may rely on groundwater resources.

Erosion Control: Adequate water infiltration helps to control soil erosion in prairies. When rainwater infiltrates the soil, it reduces surface runoff, which, in turn, minimizes the risk of soil erosion. This is particularly important in preventing the loss of fertile topsoil and maintaining the integrity of the prairie landscape.

Nutrient Cycling: Water infiltration is closely linked to nutrient cycling in prairies. It helps transport essential nutrients through the soil profile, making them available to plant roots. This process supports the nutrient requirements of the diverse plant species in prairies and contributes to the overall nutrient cycling within the ecosystem.

Biodiversity Support: Prairie ecosystems are characterized by a rich diversity of plant and animal species. Adequate water infiltration ensures the availability of suitable habitats for various organisms by maintaining soil moisture levels. This, in turn, supports the biodiversity of prairies.

Resilience to Drought: Infiltrated water stored in the soil provides a buffer against drought conditions. Prairie vegetation has adapted to periodic dry spells, and sufficient soil moisture enhances the resilience of prairies to drought by supporting plant survival during periods of water scarcity.

Temperature Regulation: Water infiltration can have a moderating effect on soil temperatures. Moist soils tend to have more stable temperatures than dry soils, contributing to a more favorable environment for plant growth and microbial activity in prairies.

Wildlife Habitat: Adequate soil moisture resulting from water infiltration supports a variety of invertebrates, amphibians, and other wildlife that depend on the prairie ecosystem. These organisms, in turn, contribute to the overall ecological balance of the prairie.

In summary, water infiltration is essential for maintaining the ecological balance, biodiversity, and overall health of prairie ecosystems. It supports plant growth, prevents erosion, contributes to nutrient cycling, and provides critical habitats for a diverse array of species.